Trump’s First Black Female Judicial Nominee a Bipartisan Pick

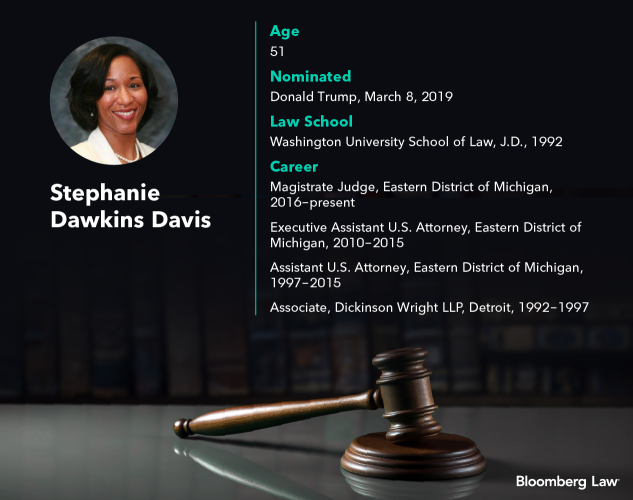

Stephanie Dawkins Davis is Donald Trump’s first black female judicial nominee, and her bipartisan appointment comes amid the contentious drive by the president and his Senate allies to reshape the federal courts.

The magistrate judge and former federal prosecutor will appear this week before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions about her nomination to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, which includes Detroit.

“She has a strong intellect, tireless work ethic and sound judgment,” said Barbara McQuade, a former U.S. attorney for that Michigan district who supervised Davis.

The GOP-led Senate has accelerated the pace of Trump nominations and Senate confirmations at the expense of bipartisan cooperation, Democrats complain.

More than 100 district and circuit court judges have been confirmed since Trump took office.

Partisan rancor over judicial selections escalated this spring when Republicans changed Senate rules to expedite votes for district court appointments over fierce Democratic objection. The GOP also is excluding circuit nominees from the so-called “blue slip” tradition of only moving forward on judicial nominees supported by both home-state senators.

Davis’s nomination is a bipartisan affair. The Trump Administration negotiated with both Michigan senators, Democrats Gary Peters and Debbie Stabenow, before putting her name forward, the Detroit News reported.

She’s the first of two black female judicial nominees advanced by Trump, whose selections so far are mainly white and male. Ada Brown has been nominated to the Northern District of Texas.

Barack Obama appointed 26 black women to the bench in eight years, while Trump has seen one black nominee confirmed, Terry Moorer of the Southern District of Alabama.